Bison Conservation: Hope for the Future

With Wes Olson, everything begins and ends with a story.

“They annoyed me,” Wes said, when we asked why he began his deep dive into bison, one of North America’s most revered mammals. “Before my career as a Park Warden, I was working as a Wildlife Technician in Northern Alberta and the Yukon, doing population counts of ungulates like muskox, moose and grizzlies. We flew around in a helicopter and if it had four legs, we counted it. When I saw bison for the first time, I realized I knew nothing about them—and that annoyed me. That’s when I began my deep dive; the more I learned, the more I wanted to know. Bison are a complex animal living in a complex society interacting with other species in complex ways, and 30+ years later, I still find that fascinating.”

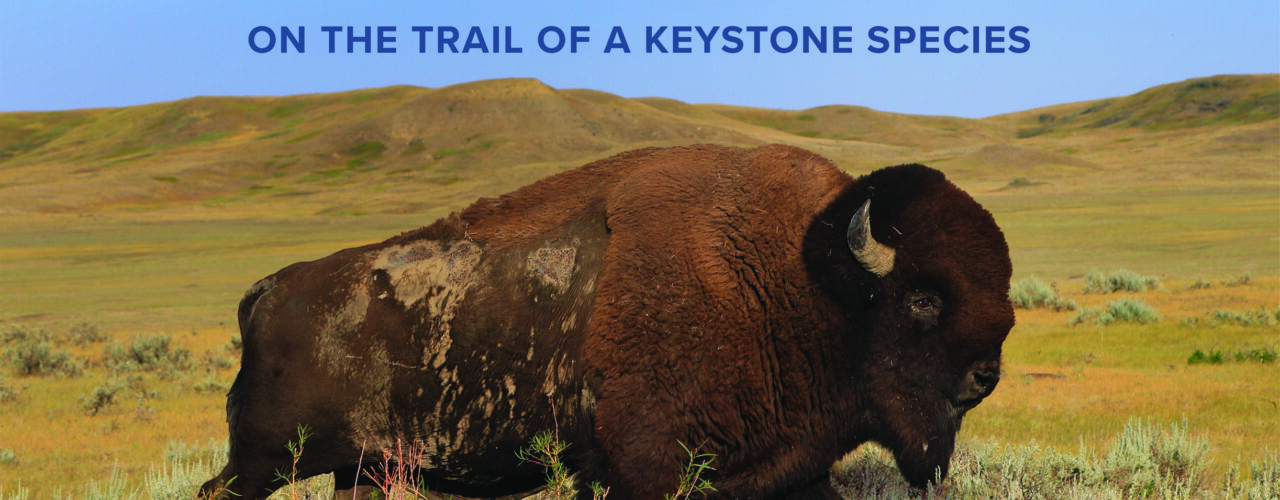

The Ecological Buffalo

At almost 300 pages, Olson’s latest book, The Ecological Buffalo, On the Trail of a Keystone Species, is equally engaging. Researched, written and photographed by Wes and his wife Johane Janelle over the course of 14 years, the book is a rigorous and comprehensive story of bison and their ecological impact on the Great Plains. Wes and Johane have traveled to almost every public, national, Federal, State and Provincial park in North America, capturing thousands of photographs and collecting a mountain of data along the way. They dedicated their research to understanding the continental influence that bison once had, and what in the future, they can continue to provide.

“The book began as an examination of bison in their habitat at Elk Island National Park,” Wes said, “but very quickly we realized this was a drop in the bucket of the story bison had to tell. So, we spread our focus over the entire continent, examining the relationships bison have with other species, from insects to ungulates and everything in between.”

The Ecological Buffalo is organized into 14 chapters separated by stunning full colour photographs that tell a story unto themselves. All the photos are captioned, as are illustrations and infographics created by Wes. “We intentionally layered the information so people can actually flip through it and be accidentally educated,” laughed Wes. “Pre-Covid, I used to talk to students across the country, from kindergarten to post Grad, and I always found it more effective to show rather than tell.”

The role of producers in conservation

One of the things Wes Olson loves to do is travel across Canada to talk to bison producers. “For 20 years, Johane and I had our own bison ranch, so I do understand that side of the story as well,” Wes shared. “The animal was almost extinct, and bison producers played an incredible role in bringing them back from the brink.”

“I’m encouraged by what I see,” Wes continued. “Almost every producer I speak with, got into the business partially because they wanted to contribute to bison conservation. And when I get asked if bison producers can play a role in ecological conservation, of course I tell them a story.”

“When migratory songbirds fly from South America to the Arctic, they need to safely land, hunt insects and refuel. Through their dung, bison are one of the best producers of insects in North America. One healthy patty hosts over 100 different species of insects and up to 1000 individual insects over the lifespan of the patty on the ground. On the Great Plains from Mexico to Central Canada, if these birds land in a bison pasture, they get the support they need, whether it’s Yellowstone, or a pasture with 6 animals.”

The Scoop on Bison Poop

When it comes to beef cattle, the dung story can be different. Cattle producers are rightfully concerned about parasites in their animals, regularly using antiparasitic drugs like Ivermectin. These drugs are very efficient, but they stay viable in cattle dung for months after, killing all insects that try to make a home there. So, when you think of the vast grassland ecosystems currently being grazed by cattle, it can be a hostile environment for many of these birds. And it doesn’t end there.

“Insects also help to break that dung down, so it’s a much larger issue,” Wes explains. “A bison patty can disappear from the landscape in just 3 days, putting all those nutrients back into the ground in a very short period of time. Cattle pastures often have old dung that never degrades because there are no bugs to break it down.” Of course, bison pastures can become fouled with dung as well, if producers treat their bison with antiparasitic drugs, but the prevalence of their use is less than with cattle.

Are bison really climate change heroes?

They are, according to Wes Olson and bison producers like Noble Premium Bison and Robert Johnson. Johnson recently discovered a wild prairie turnip on his land—something that hadn’t been seen there for many decades. Wes confirmed this regeneration of a dormant seed was a direct result of bison on the land.

“A bison hoof may look like a cattle hoof, but it has a much sharper edge so they scarify deeper and bring those seeds up. Once the plants germinate and grow, they end up in the dung that is spread over vast distances as the bison travel. This would account for the wild turnip reappearing on the landscape years after it had disappeared.”

Grasslands sequester more carbon than a rainforest and yet they are one of the most endangered ecosystems in the world. “By grazing bison,” Wes said, “we can keep our grasslands intact and mitigate global warming, just through carbon sequestration. Bison need less land than cattle do to thrive – you can graze 1.6 bison for every 1 cow on the landscape because of their ability to utilize the land better.”

According to Wes, bison may also eat 30% less than what a beef animal does, and what they eat stays in their digestive system up to 30% longer. That makes for some top quality dung. Given the opportunity, bison create their own rotational grazing system in that they pick and choose what they forage, leaving regenerative plants behind.

That said, the biggest threat to North America’s grasslands is the plow. “These are desperate times for farmers—from all walks of life,” said Wes. “With climate change, Covid and other hardships, they’re grasping for ways to increase their bottom line and stay in business. Turning over native prairie grasslands and planting cereal crops is seen as a solution. With only 2% of the tall grass prairie left in North America, the situation is very dire.”

A glimmer of hope

Bison conservation is a complex issue on both sides of the 49th parallel, but even more so in Canada. “The Woods bison are doing fairly well,” Wes explains, “because they live in a Northern landscape that is not densely populated with people and farming. It’s a different story for the Plains bison. All the historic ranges are occupied by people, cattle and agriculture, so the opportunity to establish new Plains bison populations is almost nonexistent.”

However, there is a glimmer of hope for increasing the Plains bison, with renewed First Nations interest to establish their own herds. “There is a movement to remove community pastures from cattle grazing and put Native-owned bison on the land,” said Wes. “Most reserves are too small to sustain a bison herd so the theory is that dozens of reserves who want bison for their food and cultural/spiritual needs can bring their animals to this one central place and manage them much like the cattle have been managed. This model of a co-op grazing pasture, similar to the Intertribal Bison Cooperative in the US, looks like it’s going ahead and will be a great benefit to First Nations, bison conservation, and the grasslands.”

But the story of Canada’s contribution to bison conservation isn’t contained to this continent.

“Back in the 90s,” began Wes, “I was contacted by Russian biologist Sergei Zimov who wanted to create a grassland park in Siberia. At the end of the Ice Age, Siberia was a dry grassland like Mongolia or the central great plains. Changes in climate (and absence of large hooved animals) caused it to become a permafrost environment. Sergei’s theory was that you could go back to that taiga environment with large hooved animals like bison, and shift it from frozen back to dry grassland. Wood bison from Elk Island National Park outside Edmonton, Alberta were shipped to Siberia as part of a conservation program. Sergei and his team successfully demonstrated that by simply putting bison back on that landscape, their hooves would scarify the surface and cause the 10,000-year-old seed bank to regenerate.”

Much like the discovery of Robert Johnson’s wild prairie turnip, the simple presence of bison is bringing life back to native grasslands around the world, and hope to conservationists and bison producers alike.

A note from Wes Olson

I want to give a huge shout out to the Canadian Bison Association for their financial contribution to printing the book. Without their donation it is unlikely that the book would have been published. You can contact the CBA to purchase your very own copy, and it’s also available on Amazon.